UPDATE: Some may have misconstrued my earlier comments as an anti-“woke” tirade—it’s not. My concerns, much like Roger and Gene’s, are with conformity and groupthink taking over film criticism, especially as social media outrage campaigns become increasingly common. Critics now risk harassment or death threats for expressing dissenting opinions. It’s this fear of backlash—not “woke” ideology or politics—that threatens the integrity of criticism. When critics self-censor to avoid pushback, it lays the groundwork for fundamentally harmful changes in the field.

The most recent example might be backlash that met Variety and Rolling Stone for not including “Sinners” in their year-end top 10 lists. The bigger picture for me is that this blowback said more about the current state of film discourse than it did about Ryan Coogler’s film — the increasingly rigid hive-mind dominating the field. What this controversy really told me was that we’re living in one big echo chamber: either you’re with us, or you’re against us.

These days, conformity is rewarded. Once a film is deemed essential by the online mob, any dissent — even a simple omission from a list — is treated as sacrilege. Critics who fail to align with the consensus are assumed to be wrong, or worse, have ulterior motives.

It has reached the point where some critics have privately told me they hesitate to rank or review certain films honestly because they fear the online reaction. The field has basically turned into a culture of enforcement.

Demanding that every respected critic must love one particular film — no matter how acclaimed — is antithetical to the entire idea of criticism. There has always been disagreement in film culture. There has always been debate. However, what we’re seeing now is something different: a demand for ideological alignment, which gets enforced via public shaming.

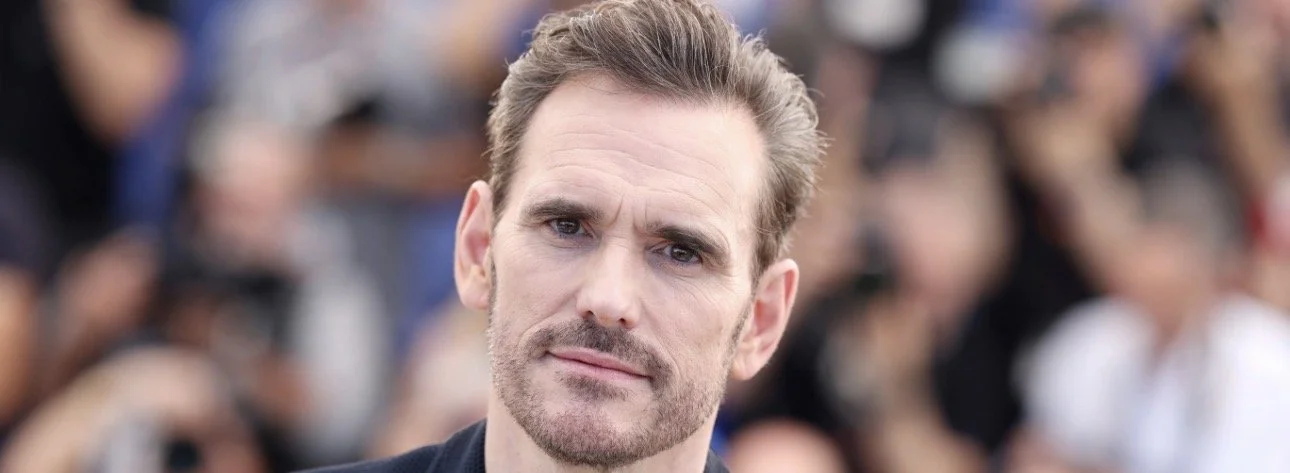

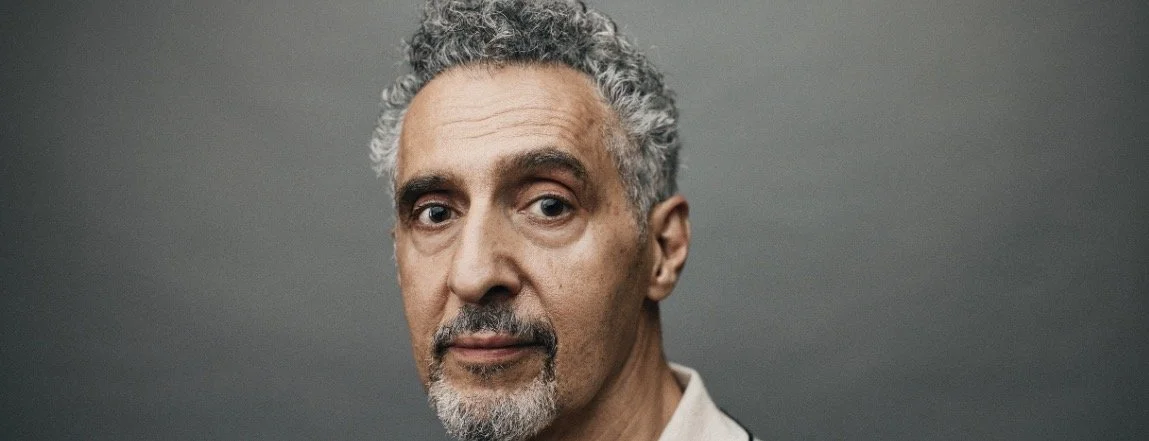

EARLIER: In the 1990s, no film critics loomed larger—or wielded more cultural influence—than Siskel & Ebert. Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert argued loudly, disagreed, and occasionally infuriated one another on air. But they shared one unshakable conviction: honest criticism mattered.

One exchange from their long-running show now feels like a prescient warning. Both men died before they could witness the current erosion of free expression in film criticism, but in a brief segment from their program, they described with startling clarity the very culture we now inhabit.

In a recently rediscovered clip, they offer advice to future critics. Siskel opens with a blunt assessment of the growing influence of political correctness:

There’s a whole new world called political correctness that’s going on. That is death to a critic to participate in that.

Ebert immediately agrees, identifying the central moral failure behind it:

Just personally wanting to be liked, wanting to go along with the group, is death to a critic.

Siskel presses the point further. Criticism, he insists, requires risk:

I’ve been given this lucky break to say what I think. If I censor myself, I’m gonna regret it.

Ebert then expands the argument beyond film criticism, turning his attention to journalism and academia. What he sees, even in the early ’90s, is a generation of young writers being trained to self-censor before they’ve learned how to think:

Political correctness is the fascism of the ’90s. It’s this rigid feeling that you have to keep your ideas within very narrow boundaries or you’ll offend someone.

For Ebert, this was not merely a stylistic problem. It was a moral one:

One of the purposes of journalism is to challenge that kind of thinking. One of the purposes of criticism is to break boundaries. It’s also one of the purposes of art.

The most damning observation comes when he describes what happens to young writers who internalize these constraints:

If they try to write politically correctly, what they’re really doing is ventriloquism. They’re not saying what they think. They’re training themselves, at a very young age, to lie.

Read today, this exchange is almost painful in its accuracy. What Siskel and Ebert did not fully anticipate was the scale of the takeover in the social media age. Read some modern-day reviews, and critics are less concerned with aesthetic judgment than with compliance. Some films are not evaluated on craftsmanship, or originality, but on whether they affirm the correct positions.

Much like modern music reviews, mainstream film criticism has largely abandoned its adversarial role. It no longer challenges audiences or artists—it polices them. Siskel and Ebert believed that both art and criticism should be allowed to offend, provoke, and take risks — today’s social media-enhanced pressure campaigns have hampered these ideals.