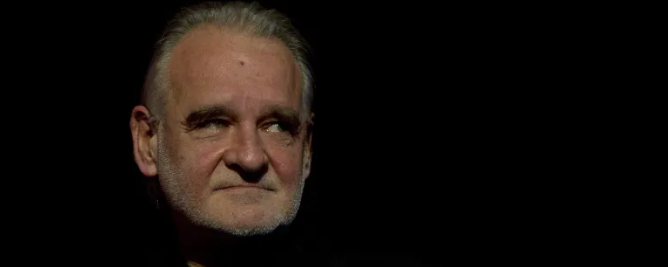

Béla Tarr, the Hungarian-born cinematic groundbreaker, has died. He was 70.

What an influence this man had on cinema. He didn’t make movies so much as he issued ultimatums. If cinema is often sold as escape, Tarr’s films were the opposite: endurance tests that dared you to look away. Very few ever made films this way. It came to the point where he was rarely invited to Cannes — his works premiered elsewhere or emerged at moments when Cannes was privileging different strains of “serious cinema.” If anything, his cinema was radically anti-Cannes.

For a certain strain of cinephile—especially the ones who came of age in the ‘90s and early 2000s—Tarr wasn’t just a director. He was a revolutionary. His influence is everywhere now. The long take renaissance. The fetishization of duration. The belief that slow cinema, when made with purpose, can be radical. Tarr didn’t invent any of this, but he made it his own. He stripped cinema down to mud, and dirt. What was left was barely plot, comfort, and catharsis.

In my world, Tarr’s legacy will largely rest on three films: “Sátántangó,”” Werckmeister Harmonies,” and “The Turin Horse.” I’ve sadly not seen the other important one, 1988’s “Damnation,” but I plan to watch it this week.

“Sátántangó” (1994) remains the centerpiece. Seven and a half hours long, shot in stark black-and-white, structured like a satanic dance that moves forward and backward in time. It is the kind of film that turns viewing into a life decision. And yet, for those who commit, it eventually becomes strangely hypnotic. Tarr observes a decaying collective farm and its spiritually bankrupt inhabitants with slow patience. Rain pours endlessly. People trudge. There’s some hope, then it dies. The film’s sheer duration isn’t a stunt—it’s the point. Once you’ve lived inside “Sátántangó,” conventional pacing in movies feels like fiction more than ever before.

Then came “Werckmeister Harmonies” (2000), arguably Tarr’s most “accessible” film and, his most haunting. Here, cosmic order and social collapse are intertwined, embodied in a drunken town prophet, a mysterious circus attraction, and one of the most devastating hospital scenes ever put to film. Tarr’s camera is still calm as ever, but there’s absolute violence behind it. Directors from Apichatpong Weerasethakul to Carlos Reygadas to Lav Diaz have been chasing this mood ever since, whether they know it or not.

And then there was “The Turin Horse” (2011), Tarr’s self-declared final film. A brutally minimalist endnote. Inspired by the legend of Nietzsche’s mental collapse after witnessing a horse being beaten, the film is stripped to the bones — a man eating boiled potatoes, getting dressed, staring into the void as the wind howls. Each day is worse than the last. Much like his other films, there is no light here. The world simply gives up. It is one of the bleakest films you will see.

Tarr’s legacy will be that of a filmmaker of silence, duration, and ambiguity. He dared his audience to stick with his films, despite there being no catharsis — you had to commit to them. In an era increasingly dominated by content, algorithms, and distraction, his films now feel almost confrontational—anti-streaming, anti-binge, anti-everything.