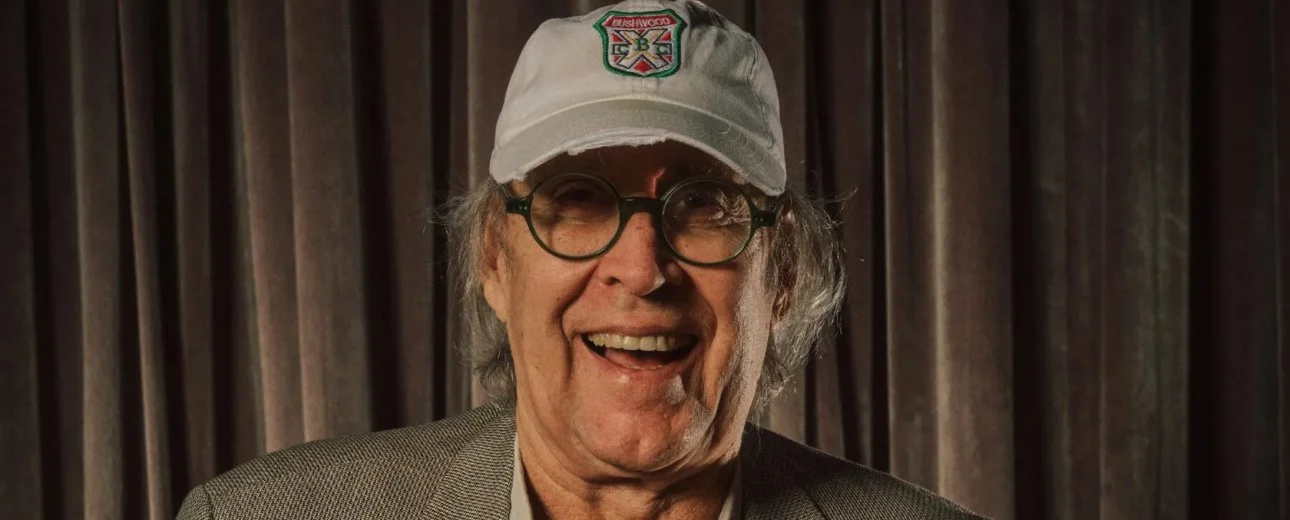

Chevy Case: comedy talent, and genuine asshole. Chase’s current PR tour has been further proof of why the man is so widely disliked by people who have had the misfortune of working with him.

He’s out there promoting a CNN documentary about his life and simply can’t help outing himself as a chronic asshole in every interview. He also refuses to apologize for the endless misdeeds, the sheer terror?l he’s perpetrated on colleagues over these last six decades.

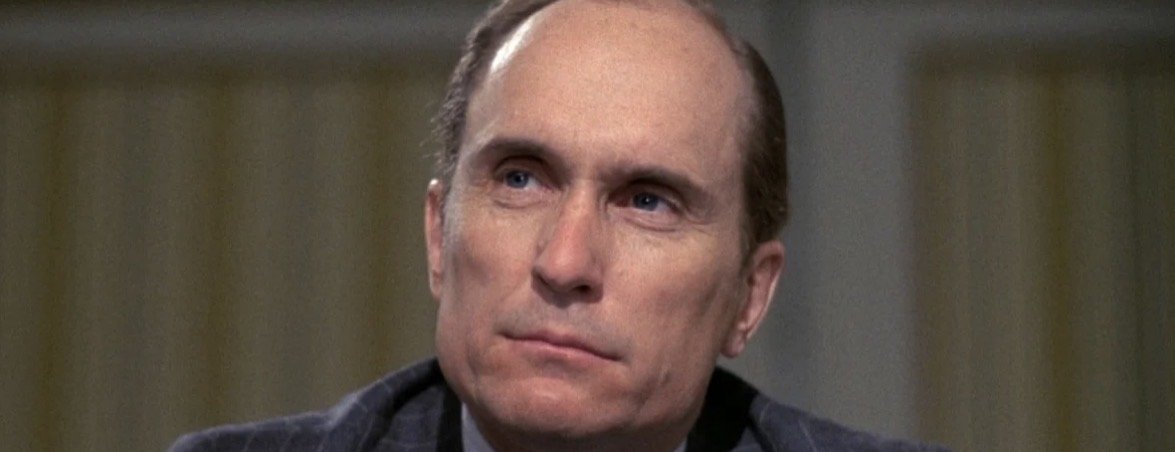

One of Chase’s most notable “victims” was John Carpenter, who famously—or infamously—said that working with Chase made him want to quit show business. The clashes they had on the set of “Memoirs of an Invisible Man.” Carpenter has bluntly called Chase “a director’s worst nightmare” and said the actor was “nearly impossible to direct” on that project, contributing significantly to why he later said the movie was the one he most “hates thinking about.”

In a recent interview with The New York Times, Chase was asked about Carpenter’s comments and attempted a classic switcheroo, insisting that he wasn’t the problem—no, it was Carpenter who was actually the douchebag, laying it out in typical Chevy Chase fashion.

“What about the part where John Carpenter said you made him want to quit the business?”

CHASE: “I don’t know what that’s all about, but he’s a crazy guy anyway.”

“So that’s about his behavior, not yours?”

CHASE: “Did he say I was an [expletive]?”

“He said you made him want to quit the business.”

CHASE: “Oh, that’s even better. If you look at those movies, they come from a guy who’s frightened, who’s unsure. I think that he mistreated other people, and that’s not good. And I try not to mistreat other people, particularly having a fame quality, because it makes them feel bad.” (Carpenter declined to comment.)

That’s a particularly rich claim coming from Chase, a man long Hell, Chase’s decades-long reputation for being an asshole goes back so far that even Cary Grant sued him for defamation in the 1980s.

Where to start? Over the years, Chase has been widely criticized by colleagues for behavior described as hostile or demeaning: during his Saturday Night Live years, cast members and writers such as Bill Murray—with whom he had a notorious on-air physical altercation—Jane Curtin, Gilda Radner, Dan Aykroyd, Al Franken, and even producer Lorne Michaels spoke publicly about his arrogance and cruelty in the writers’ room; on films like Caddyshack, co-stars Bill Murray and Rodney Dangerfield recalled constant antagonism.

Decades later on “Community,” co-stars and creators including Donald Glover, Yvette Nicole Brown, Joel McHale, Ken Jeong, and Dan Harmon described racist remarks, verbal abuse, and behavior that damaged morale and production.

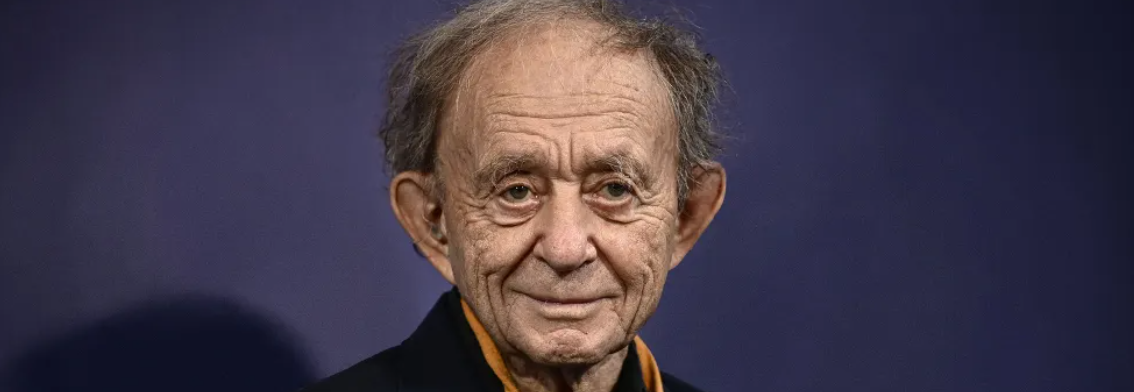

Chase rarely expresses regret; the consistency of these accounts across different eras has cemented his reputation as one of Hollywood’s most notoriously difficult personalities. Yet the comedies he made in the ’80s will live on — I’ll gladly, guilt-free, rewatch Chase gut-busters like “Vacation,” “Fletch,” and “Three Amigos.”