Well, “Eddington” is certainly an experience. If you scour through the reactions out of Cannes, they’re unsurprisingly love or hate. Raves coming in from IndieWire, Variety, Collider, Deadline, and mixed ones coming in from THR, Financial Times, The Standard, The Wrap, Screen, The Times. I’m somewhere in the middle of all this chaos.

“Eddington” opens with a smirk and closes with a clenched fist. It’s a film that begins by poking holes in the absurdity of America’s recent history, only to end up staring deep into the abyss those holes reveal.

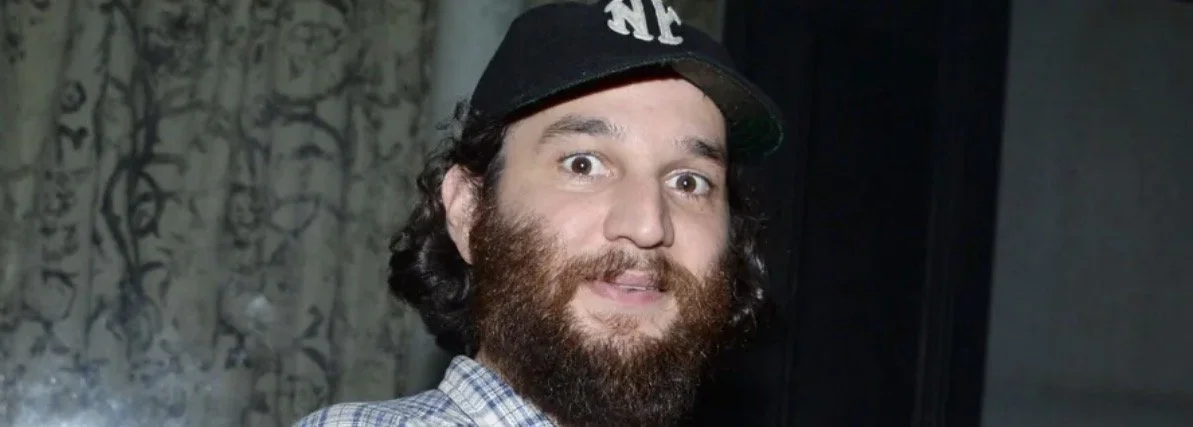

This is Aster’s most straightforward film — there’s none of the surrealism of his first three efforts (“Hereditary,” “Midsommar,” “Beau is Afraid”). It also doesn’t help that Joaquin Phoenix is severely miscast in the lead role.

Set during the early heat of the pandemic—May 2020, to be exact—the film introduces us to Sheriff Joe Cross (Joaquin Phoenix), a man forged in the cinematic lineage of American cowboys and antiheroes. Opposite him is Mayor Ted Garcia (Pedro Pascal), a slick bureaucrat — clean, composed, and vaguely suspicious. When Joe decides to run against him after a tense altercation at a grocery store over face masks, the film finds its initial premise: a COVID-era local election that quickly mutates into something darker and more chaotic.

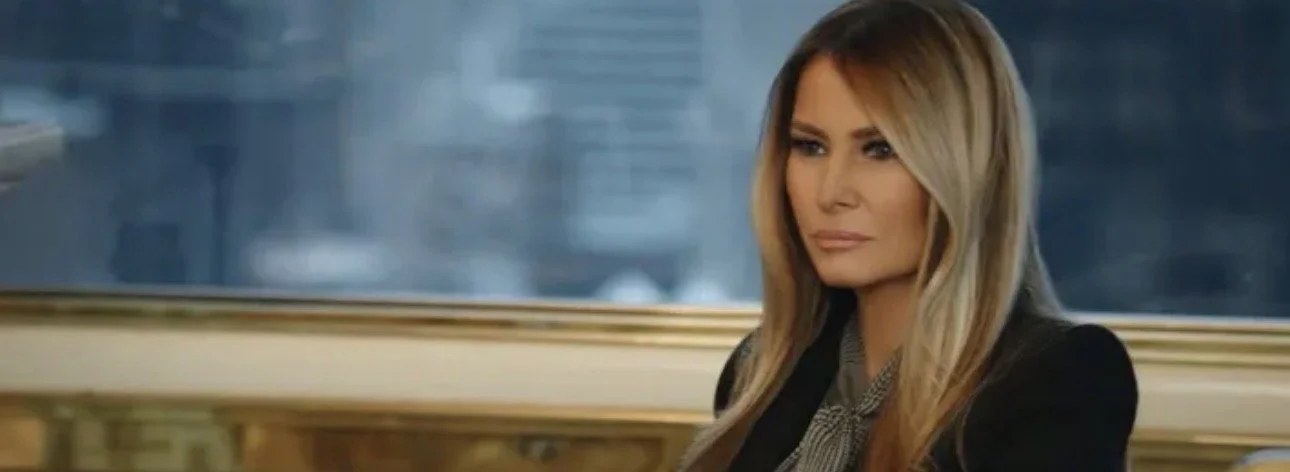

For a while, “Eddington” plays like a farce—a sharp, even gentle satire of a country losing its mind. Aster revels in sight gags and absurdity: teens flirt over Angela Davis quotes, townsfolk panic over protests that cause minimal damage, and conspiracy theories flourish. Emma Stone plays Louise, Joe’s increasingly detached wife, who falls down the internet rabbit hole. Austin Butler, in a useless role, shows up as a greasy, charismatic guru, delivering deranged monologues with the casual flair of a late-night infomercial host.

The first half of “Eddington” doesn’t hit the mark, content to observe America’s descent into ideological chaos from a distance. The stakes feel low, almost farcical—until they don’t.

Some characters—Stone’s Louise and Pascal’s Garcia—feel more like metaphors than people. The film’s initial approach to symbolism—throwing in Fauci, Clinton, Tucker Carlson, and ANTIFA— is overcooked and lacking substance. Aster is trying to say something about everything, and sometimes ends up saying not enough about anything. The ambition is admirable, the execution occasionally overcooked.

It’s about halfway through when “Eddington” changes. Joe, flailing in his campaign, levels a devastating accusation against Garcia that turns the tide not only of the election but of the film itself. What had been comic becomes tragic. The satire morphs into a neo-western, a political thriller, and finally, something close to horror.

Violence erupts. The language of protest, of tribalism, of unresolved history becomes literal. The murder that erupts between jurisdictions—a patch of land caught between state and Native authority—reframes the conflict in broader, older terms. Suddenly, this isn’t just about one sheriff or one mayor. It’s about bloodshed.

Aster, seems to find his stride when the film leaves behind cleverness and embraces the grotesque. He’s always been interested in decay—familial, spiritual, social—and here he doesn’t pull back.

I admired the swing. Few films dare to be this messy, this provocative. In a cinematic culture content with safe stories and sanitized emotions, “Eddington” feels like a slap in the face.