I haven’t read Nick Tosches’ book, but it can’t possibly be this vulgar, this bruisingly literal, this operatically excessive. Julian Schnabel turns Tosches’ story into blood-soaked, pulp self-mythologizing, and poor Oscar Isaac—one of the best actors we got—looks stranded, as if he’s been cast in a grindhouse movie.

Schnabel’s “In the Hand of Dante” is the sort of movie that announces its importance before it’s even begun—and then spends the next two and a half hours trying to convince you it is. The walkouts at Venice’s Salle Darsena started twenty minutes in, and they didn’t miss a thing.

‘Dante’ has that same vibe of unchecked indulgence as Coppola’s “Megalopolis,” except at least Coppola’s film, willfully or not, turned out to be funny. Hers’s Schnabel, a veteran director, intoxicated by freedom, enthralled by ambition, and oblivious to how disjointed, pretentious, and simply baffling the results are.

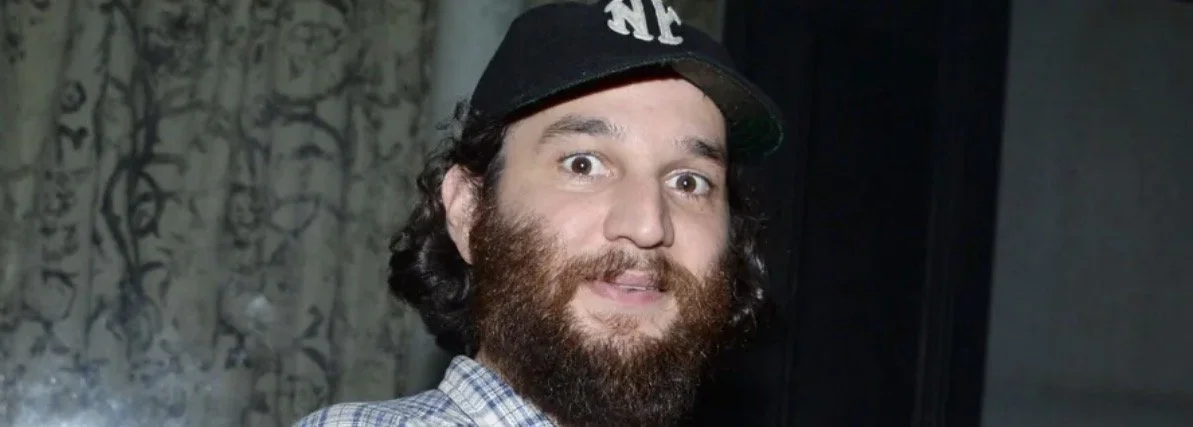

He has assembled a cast that looks like it came from someone’s wild dream—Oscar Isaac, Gal Gadot, Gerard Butler, Jason Momoa, Al Pacino, John Malkovich, Franco Nero. Martin Scorsese shows up for a brief gag of a cameo, and it’s one of the few times the movie has a pulse. Al Pacino has a few juicy minutes early on, sparring with a young Tosches, but then it’s back to the endless shootings.

Gerard Butler, playing a hitman with all the subtlety of a wet boot, seems to have wandered in from a different film entirely; his character is repellently grotesque—so much so that the audience practically cheers when Isaac finally ices him.

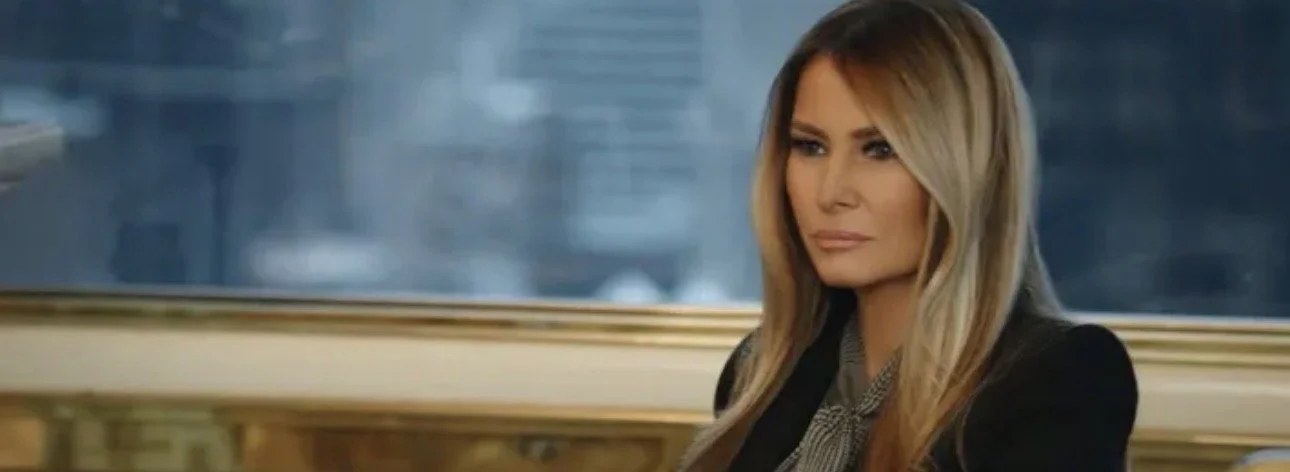

The film’s narrative swings wildly between centuries and identities. Isaac doubles as Dante Alighieri and as Tosches, the journalist who once wrote the novel on which the movie is based. Gadot plays both Dante’s wife and Tosches’ assistant. There are moments of reincarnation, literary studies, gangland intrigue, and Vatican conspiracies. It’s honestly not worth explaining.

A lot has been reported about Schnabel’s clashes with the producers, who pushed for no black-and-white sequences and a runtime under two hours. Schnabel outright ignored them. The Venice cut ran a sprawling 150 minutes—an agonizing stretch for a film that never manages to justify its own length.

Schnabel clearly believes he’s delivering a grand statement on art, faith, and mortality, but what makes it to the screen is scattershot.