You’ve probably read—or at least overheard—the gushes and raves about Chloé Zhao’s “Hamnet” at Telluride, all the talk of it as a best-picture contender. Is the hype justified? Well… yes, and no. This isn’t the flawless masterpiece the critics want you to believe, but I’ll tell you one thing: it has the finest ending of any film I’ve seen this year.

Maggie O’Farrell’s novel “Hamnet” has been described as dense, lyrical, almost impossibly detailed, it seemed like the sort of book that could never survive translation to film. Yet Zhao, who has always been a careful observer of people and landscape, has taken a stab at it—and the result is, against all odds, quietly moving, occasionally stale, but with a closing stretch that lingers in the memory. I’m telling you, that last stretch meaningfully pays off the slow buildup, and elevates the entire film in the process.

Zhao is a natural for this terrain; her eye for nature and the aches of human longing etc. However, “Hamnet” asks for a sort of formal elegance Zhao hasn’t always worked in.

The humble, intimate charm of “Nomadland” or “The Ride” sometimes feels missing here; instead, the film feels prestige-minded, the kind of effort that knows it wants to be taken seriously. Yet, even so, Zhao’s compassion, curiosity carries it through. This is a story about loss, about grief and creation—and Zhao never lets it tip into mawkish sentiment.

The premise is intriguing. Shakespeare’s son Hamnet died young, and his death is thought to have inspired, at least in title, “Hamlet.” O’Farrell imagines that writing the play was a way for Shakespeare to grieve; Zhao’s film has moments where the literalness of the idea feels a bit much, but for the most part, Zhao convinces. And what matters is the emotional truth she eventually goes to: the transformative power of art.

“Hamnet” has other flaws. The courtship of William (Paul Mescal) and Agnes Hathaway (Jessie Buckley) is slow: the shy tutor drawn to Agnes’s eccentricity, the village whispers that mark her as an outsider. Zhao lingers here, perhaps too long, when we ache to know the boy before he is lost, to live with Hamnet alongside his siblings, to feel that absence with sharper clarity.

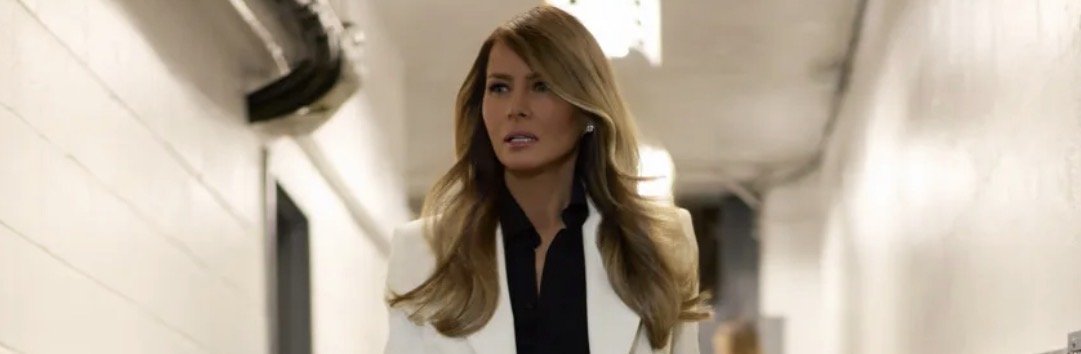

Where Zhao sometimes falters, her lead more than makes up for it. Buckley is extraordinary, inhabiting Agnes with a presence that feels both elemental and infinite. When she carries the film to its final, shattering minutes, she channels sorrow and hope, rendering grief as something living, almost too real. Mescal, despite having far less screen time, delivers a commendable performance, though it remains unremarkable until he elevates his game in the final scenes.

About that finale it’s transcendent. Max Richter’s On the Nature of Daylight has been used before, and yet here it feels justified. It’s at that very moment that Zhao’s film reveals its purpose: the intimate grief of a family becomes the nucleus for enduring art. The private sorrow of Agnes and William blossoms into something universal. That alone redeems the film.

What the many raves fail to mention is the uneven pacing, moments that feel slightly coerced. Yet in the closing moments, when the story is at its most elemental, you realize Zhao has done something remarkable. Making you feel, all at once, human fragility and resilience.

A great ending can do what the rest of a film sometimes cannot: it can give the whole thing a heartbeat, a pulse that lingers after the credits roll. Even if the story has been slow, uneven, or weighed down, a finale can make the whole film feel necessary,. That is what Zhao’s “Hamnet” achieves: the film’s final moments turn grief into something universal, quiet and heartbreaking at once. It’s a real stunner.