NOTE: I’ll try to sort through some of the reviews, and update as more come along.

IndieWire (B), The Daily Beast (Negative),

Slant (2/4), EW (B+), THR (Positive), Variety (Positive), The New Yorker (Negative), The AV Club (B-), The Wrap (Positive), Screen (Positive)

Celine Song’s “Materialists” isn’t personal in the way her debut “Past Lives” was. There’s no clear autobiographical thread this time—just a self-aware riff on the classic love triangle rom-com, dressed up in the aesthetics of an A24 indie. Song’s interest in genre tropes overshadows her characters, and what starts out as a high-concept dating satire ends up more schematic than sincere.

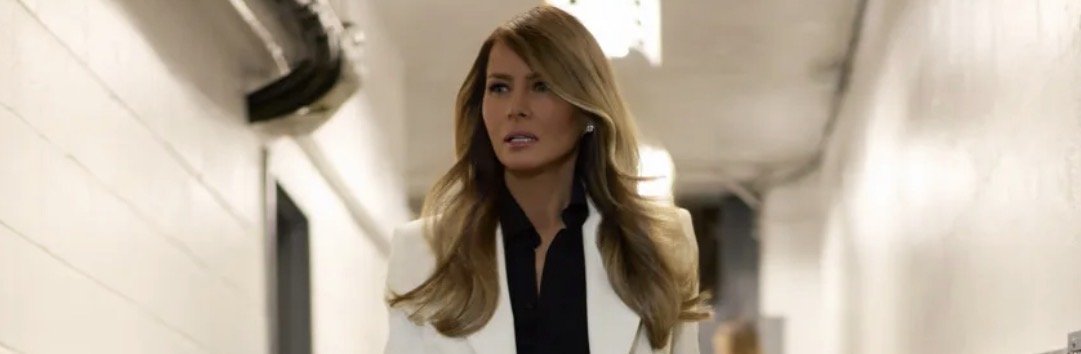

“Materialists,” her sophomore effort, stars Dakota Johnson as Lucy, a polished professional matchmaker who works for a high-end dating service that promises rich, picky clients the dream: that they’ll marry the love of their life. The twist? The “dream” now comes with a checklist—height, salary, education, and a side of emotional intelligence. Clients treat it like ordering from a catalog. Welcome to dating in 2025.

Once again, the setup involves a woman torn between two men: Lucy finds herself caught between Harry (Pedro Pascal), a walking finance fantasy with an Upper East Side lifestyle, and John (Chris Evans), the ex-boyfriend she left behind—a broke actor now moonlighting as a cater waiter. The banter is playful, and for a while, “Materialists” works like a charmful antidote to rom-com tropes.

Song seems to know what’s she’s writing about as well, which means that “Materialists” gets the small details right: the subtle snobbery of dating culture, the business-like tone of modern matchmaking, the class anxieties tucked into every conversation.

Visually, it’s grainy slick. Shabier Kirchner’s cinematography gives the film a clean texture, but while the camera gets the surfaces right, the script loses emotional footing as it tries to wrap things up. Characters start sounding less like real people and more like mouthpieces for an argument about modern love and class mobility.

The trouble is, “Materialists” wants to be a grounded, mature take on the genre, but in the end can’t help but resort back to those same cliches. Song clearly wants to wrestle with big questions—what love means, how money warps it—but “Materialists” can’t help falling back on familiar tricks: dramatic reveals, emotional speeches, a neat final act that ties things up just too perfectly. The movie tries to smooth it out.

By the third act, Lucy’s transformation feels forced, not earned. The film wants to interrogate the rom-com formula, but ends up falling back on it. What “Materialists” ultimately proves is that it’s not enough to take rom-com clichés and give them an indie polish. You still need charm, character, conflict—something alive under the surface.

Song clearly has ideas, and “Past Lives,” although I wasn’t as infatuated by it as others, showed she knows how to handle emotional complexity. But here, she’s stuck between two modes and commits to neither. The result is a film about love and money that ends up feeling oddly cheap.