Paul Greengrass makes movies like a man chasing after panic with a camera, and in “The Lost Bus” he has a doozy of a subject: the 2018 Camp Fire, that inferno which turned a California town, Paraside, into ash in less than a day.

The reviews so far are good. Vulture, Variety, TheWrap, Deadline, Screen. It’s no secret Greengrass’ glory days might be behind him —“Bloody Sunday,” “United 93,” “The Bourne Ultimatum” — but “The Lost Bus,” which plays like a well-made ‘90s disaster flick, is probably his best work since 2012’s “Captain Phillips.”

Greengrass isn’t subtle—he never has been—but subtlety isn’t what people go to him for. He gives you the nightmare head-on, the way a disaster actually feels when you’re in it: disorienting, too fast, a little numbing. Matthew McConaughey and America Ferrera do the impossible—drive a rickety school bus full of kids straight through hell.

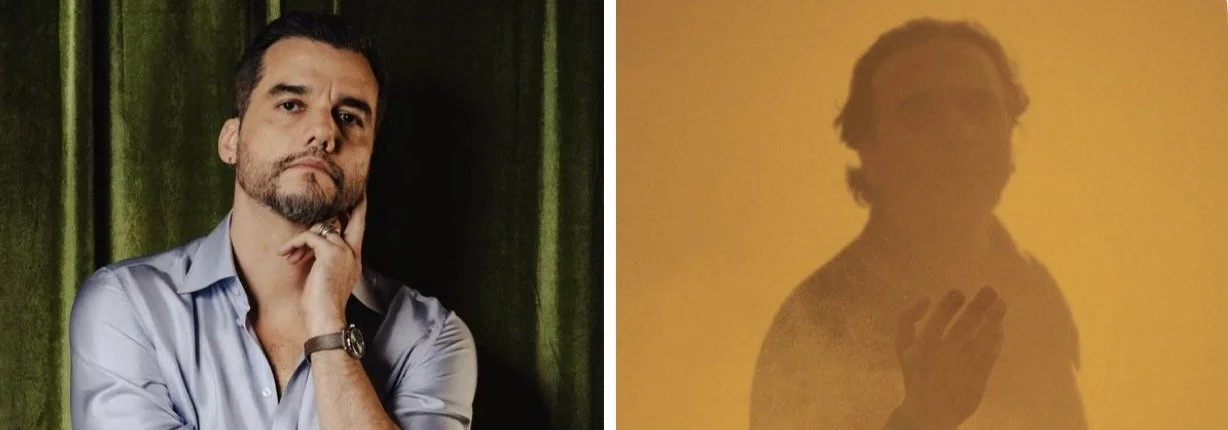

McConaughey, returning after six years away, doesn’t look like the glossy movie star you remember. He’s all slump and drawl, worn down by divorce, debt, and moving back in with his ill mother. Greengrass makes you sit with his misery before the flames even arrive—he kills off his sick dog in the opening minutes, and it’s manipulative. However, McConaughey doesn’t play it like a setup. He plays it like a man who’s had enough, and that rawness carries through when the fire erupts. Without him, Greengrass’ film might not work.

When it does, Greengrass does what he’s always done best: he puts the camera inside the hellish fire. The inferno is everywhere and nowhere at once, a kind of living, suffocating organism. Pål Ulvik Rokseth’s handheld photography makes you feel as though you’re trapped on that bus, breathing in smoke. James Newton Howard’s score crashes and booms—too much, sometimes—but it does blend with Greengrass’ style. Apple is streaming this thing, but the pity is that it begs for a screen that makes you sweat.

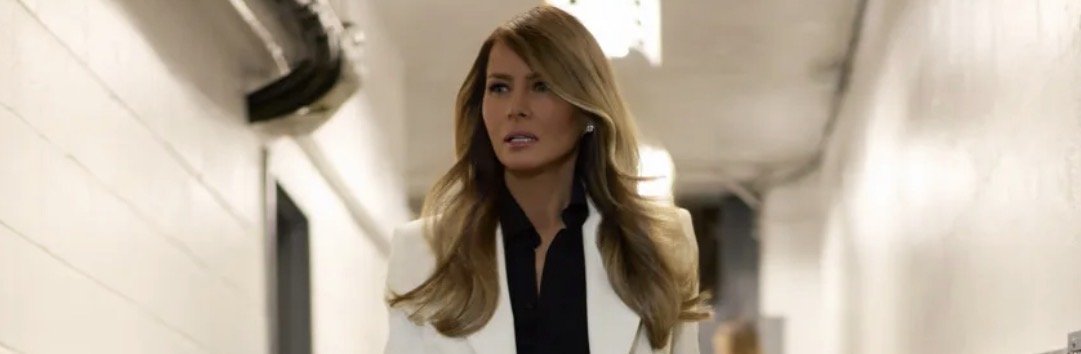

America Ferrera is wonderful here, sharp and practical as the teacher who won’t let her kids see how terrified she is. The two of them—McConaughey with his haunted weariness, Ferrera with her strength—make you believe in the heroism. There’s a moment when she sneaks out of the bus and into the fires to scavenge water, her body trembling from the heat, and it feels almost unbearable to witness.

Around the edges, the film tries to broaden the story. Yul Vazquez turns up as a fire chief wrestling with the slowed-down bureaucratic response while the flames close in, and Greengrass isn’t shy in showcasing the negligence behind the catastrophe. However, what matters to Greengrass, and to us, is that bus barreling through an apocalypse, children huddled in terror, and the two adults who won’t let them die.

“The Lost Bus” is harrowing, yes, but it’s also blunt and occasionally shameless in its depiction of this tragedy. Greengrass doesn’t trust us to feel without being shoved, and the film sometimes teeters on the edge of disaster-movie cliché. But when McConaughey grips that wheel, sweat pouring off him as the windshield fills with flames, you stop caring about the clichés. You’re too busy holding your breath.