I’m an admirer of Brazilian filmmaker Kleber Mendonça Filho, whose “Aquarius” and “Bacurau” pulse with life, rebellion, and a distinct cinematic voice. But with his latest, “The Secret Agent,” which premiered here at Cannes to glowing notices, I found myself curiously detached by some of its lengthy 2 hour 39 minute runtime.

In fact, I wasn’t alone. At the Lumière Theater screening, the loudest reactions were snores. You could practically hear the room nodding off. Over on Letterboxd, reactions range from bewildered to blunt: “boring,” many declare. And yet, “The Secret Agent” currently boasts an 86 on Metacritic, based on six early reviews. That number may well come down as more critics weigh in, but for now, it’s a curious disconnect between the critical establishment and the audience in the dark.

Mendonça Filho is too talented a director to dismiss outright — there are surely ideas and images here that deserve unpacking. But for me, this particular dispatch from his cinematic universe felt less like a thrilling covert operation and more like a long night stakeout… with nothing to report.

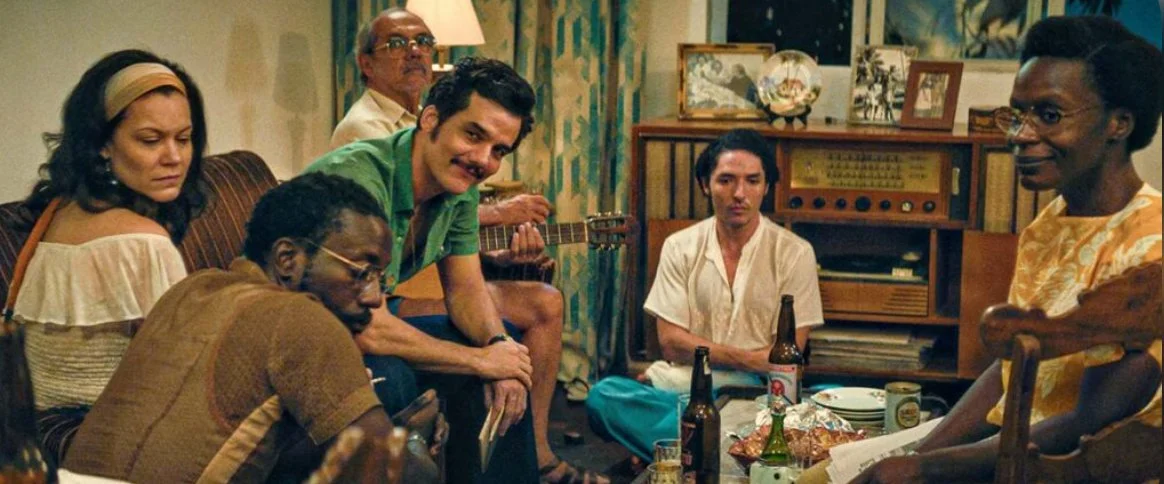

“The Secret Agent” begins not with a bang, but with a kind of atmospheric murmur—a slow descent into the moral fog of 1977 Brazil, where the sun blazes and the soul flickers. For Mendonça Filho, a filmmaker of undeniable intelligence and command, this is not an easy film, nor a hurried one. It moves with the hushed caution of a man being followed. Or, perhaps more fittingly, a man who thinks he’s being followed.

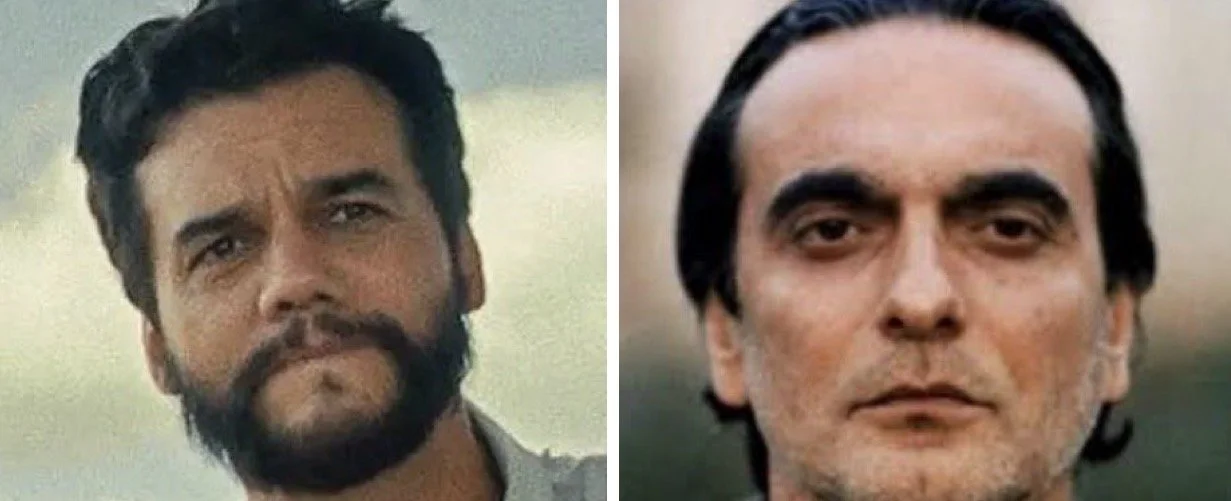

The protagonist, Marcelo—played with quiet anguish by Wagner Moura—is a university researcher caught in the shadows of Brazil’s military dictatorship. He’s a man who seems to be perpetually bracing for something: a phone call, a knock at the door, the inevitable unraveling. He’s also, it turns out, not quite who we think he is, though the film takes its time—nearly two hours—before revealing his true name, Armando, and the threat that trails him.

For most of its 159-minute runtime, “The Secret Agent” drifts through Brazil with a kind of poetic lethargy, touching on conversations, memories, and encounters that hint at surveillance and danger, but rarely deliver it. Mendonça Filho is less interested in plot than in tone. He is, unmistakably, a sensualist, and this film is a tapestry of sounds, glances, and textures. Yet there is also the sense that we are waiting for spark, a long-promised explosion. And when it finally arrives—in a final act marked by bullets and breathless chase—it’s hard not to wonder if the wait was too long, or if the film could have found more purpose in its wandering.

There is craft here. There is ambition. And there are moments that shimmer with dark lyricism. But I confess: I found the journey difficult, at times tedious, even irritating.

There are, for the record, some surreal flourishes—a severed leg, a shark reference or two, and a frankness about sexuality that feels at once honest and somewhat random. But like much of the film, these elements suggest meaning without quite securing it.

In the end, “The Secret Agent” is a movie that I admired more than I enjoyed, a film made by a director I respect but whose choices here left me cold. There’s no denying Mendonça Filho’s skill or sincerity. But for all its political undercurrents and thematic gravity, the film floats.